Much has been written about the Italian Futurist Luigi Russolo, most of it focused on his influential manifesto, The Art of Noises (1913), and the subsequent design and performances of his intonarumori (noise-intoner) instruments. Whether rightly or wrongly, Russolo is often considered, as Far Out magazine put it, “the pioneer of experimental music.”

To restrict Russolo to such a single and significant role is to simplify him, however. Before concentrating on a new approach to music, Russolo was an active fine artist, creating some of the first Futurist paintings, those which helped provide the movement with a visual template. He was also a prominent Futurist agitator, signing his name to other of the movement’s manifestos, and participated in some of its most notable public disturbances. He was an excellent prose writer, and a serious composer. In his later years, he returned to painting. He also returned to live in Italy from France in 1933, just as Mussolini’s dictatorial grip on his home country was tightening alongside Hitler’s rule in neighboring Germany, raising serious questions about his ties, per most Futurists, to fascism.

This article is adapted and expanded from an essay I wrote as part of an ongoing University course on Performance History: The 20th Century. More so than usual, I’d recommend this weekend article be read on a laptop rather than a phone, and at leisure. It is long. It is also thorough. Enjoy! And if you do enjoy, please subscribe for twice-weekly articles.

Born in a town near Venice in 1885, Luigi Carlo Filippo Russolo hailed from a musical family; his father was organist at the town cathedral and his two elder brothers both attended the Giuseppe Verdi Conservatory in Milan, to which city Luigi followed them in 1901. There, he took courses at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts and, significantly, served as an apprentice on the restoration of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper between 1904-08. Among his early paintings was a self-portrait that showed him staring wide-eyed directly out of the canvas, surrounded in the background by shadowy skulls, suggesting an interest in symbolism and the occult that would remain present throughout his career.

Invited to exhibit at the annual Black and White Exhibition in Milan in 1909, Russolo met the Futurist painters Umberto Boccioni and Carlo Carrà. Futurism was in its early burst of youth, the original manifesto having only been published (in Le Figaro, a French newspaper) by Felippo Tomasso Marinetti in February of that year.

Marinetti was an excellent poet and prose writer, a supreme and supremely confident self-publicist and networker, a cultural provocateur who sought to translate his beliefs into political action, and blessed by inheritance to have the wealth to indulge in the Parisian milieu and enable Futurism its high-profile launch. His 11-point manifesto, prefaced by an allegorical piece of writing, raged against Italian tradition, the peoples’ constant homage to a Romantic past that held little relevance in the present, let alone any purpose for the future.

Accordingly, he vowed that his Futurists would “destroy the museums, libraries, academies of every kind.” He heralded instead “the beauty of speed,” and sought to “hymn the man at the wheel.” Claiming to speak for a group of visionaries of whom “The oldest of us is thirty,” Marinetti asserted of his fellow Futurists, ominously: “We will glorify war—the world’s only hygiene—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman.”

Regardless of the nationalistic, militaristic, and patriarchal attitudes that accompanied Futurism, the cultural-political atmosphere of the time, along with the groundwork laid by the avant-garde and expressionist movements, was such that Futurism immediately took hold with an elite group of Italian artists.

Luigi Russolo was prominent among them. He quickly attached his name to the “Manifesto of Futurist Painters,” first published as a leaflet in February 1910, the same year he befriended Marinetti personally. His signature appeared alongside those of Boccioni and Carrà, plus Gino Severini and, significantly, the established Giacomo Balla, teacher of both Severini and Boccioni. Using similar language to Marinetti’s manifesto, these artists collectively decried the “spineless worshipping of old canvases,” committing to seek inspiration instead from “contemporary life,” specifically “speedy communication,” “transatlantic liners,” dreadnoughts, airplanes and submarines.

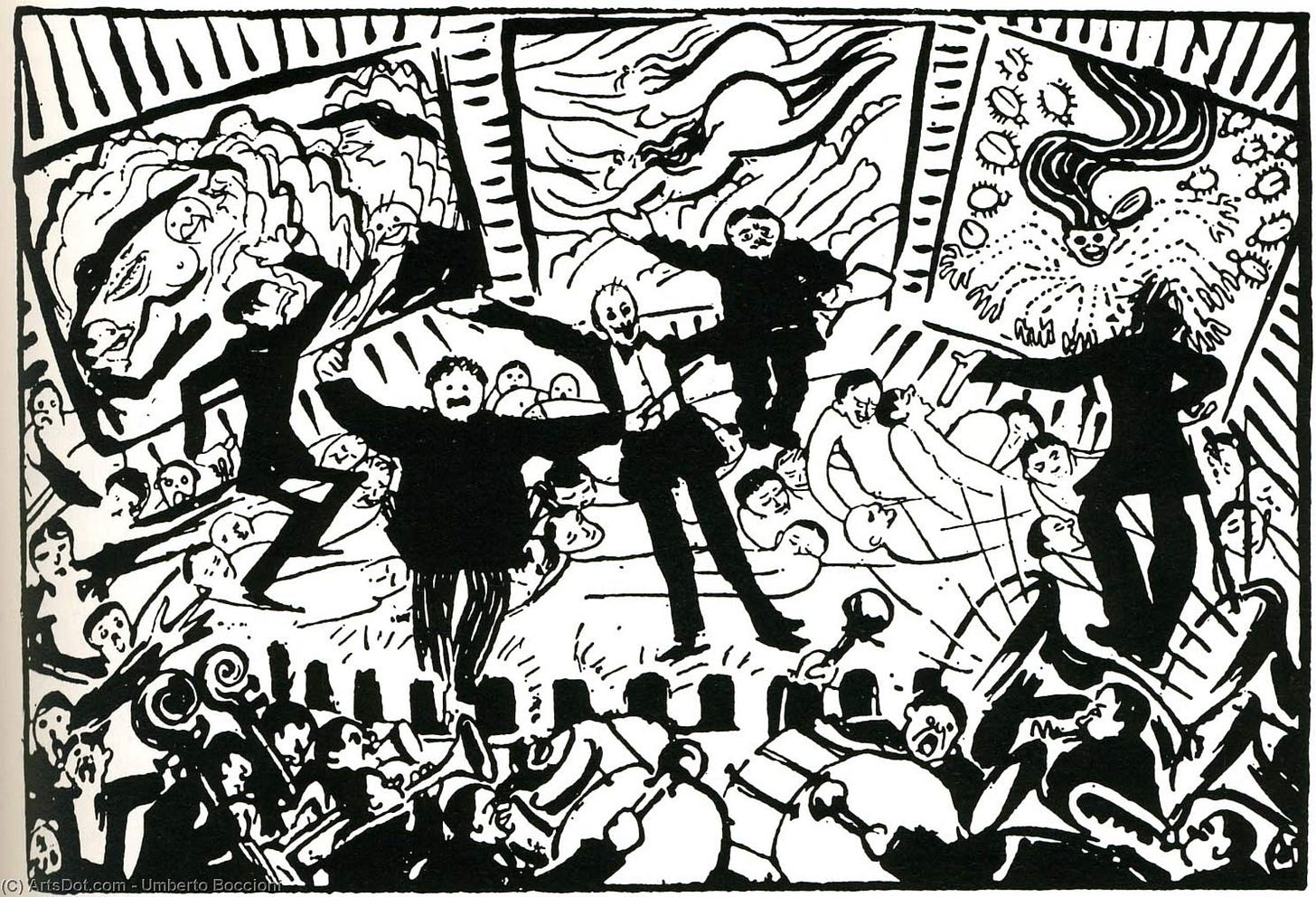

If such desires seem reasonable in hindsight, their mode of delivery invited hostility at the time. According to the same five artists in their “Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting,” published two months later, the first public recitation of the February manifesto, at the Chiarella Theater in Turin on March 18 1910, provoked a riot that they labeled “the Battle of Turin,” in which they claimed to have “exchanged almost as many knocks as we did ideas.” Then again, violent rhetoric was the Futurist stock-in-trade; “No work without an aggressive character can be a masterpiece,” said Marinetti in his original manifesto.

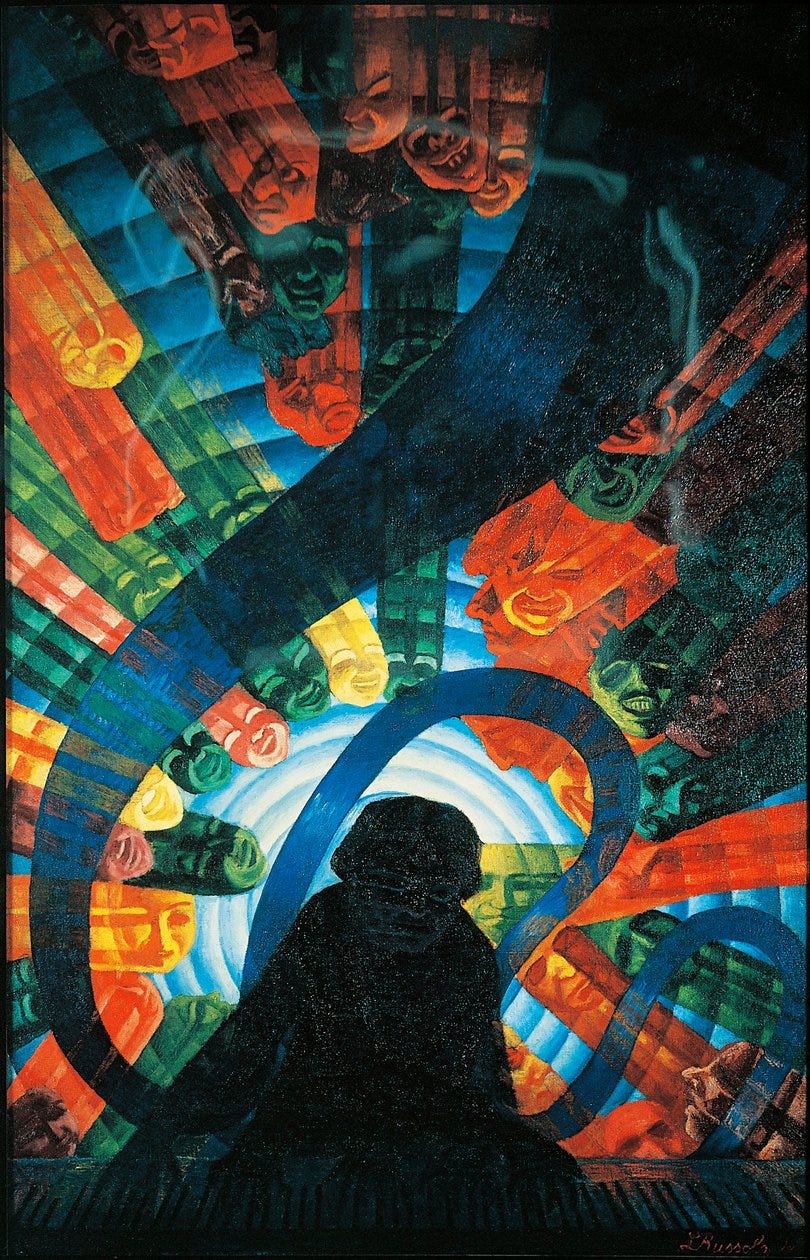

Though he was active in these altercations, Russolo was at heart a serious artist. Christine Poggi, in an essay entitled “The Futurist Noise Machine,” wrote that the Futurist painters were “fascinated by the seemingly unmediated power of sound, and sought to evoke or enact its effects by visual means” but that, “among the problems they faced was how to evoke the temporal flow of sound, its movements and rhythms, its shocks and vibrations.” It was Russolo who first succeeded, and it is no coincidence that one of the paintings in which he did so, unveiled at the first group showing of Futurist-referenced paintings, in Milan in 1911, was entitled Music. Portraying a shadowy figure at a keyboard, with masked faces resonating behind streaks of primary/rainbow colors emanating upwards and outwards, the painting owes something to both expressionist and symbolism styles but is evidently seeking a fresh form of its own.

Over the following year, Russolo began experimenting with the forward - i.e. Futurist - motion of geometric lines, the further use of bold, bright colors, and the abandonment of any hint at portraiture or landscape. Both The Revolt (1911) and Dynamism of an Automobile (1912-13, below) clearly embodied the ideas laid out in the pair of Futurist Painters manifestos, with a celebration of violence in the former and of speed and machinery in the latter, and as such can be heralded for helping craft a new form of painting.[ii]

But while these were arguably the works of a great artist, they were not necessarily Great Art, and Russolo appears to have recognized that his calling lay as much in his musical abilities as his painterly ones. Two specific writings by his fellow Futurists, both in 1912, pointed him towards this realization. Firstly, the composer Batilla Patella published his “Manifesto of Futurist Musicians,” in which he complemented Germany’s “genius” composer Wagner, and celebrated both England’s Elgar for seeking to “destroy the past,” and Russia’s Mussorgsky for consigning “tradition … to oblivion,” before pouring contempt upon Italy’s “vegetating schools, conservatories and academies.” Taking issue with the music publishers in particular – the gatekeepers of their day – Pratella showed foresight as well as courage in his own eleven bullet points, proclaiming that “the reign of the singer must end” (i.e. the role of the singer should be no greater than that of any instrument in the orchestra), and that, “given the breakdown in faith,” “scared music” no longer had “any reason to exist.” Working within the framework of western historical instruments in a country that seemed hopelessly betrothed to its history, Pratella wanted to wake up the cognoscenti and engage them in new approaches to orchestral music.

Meantime, Marinetti’s hunger for war led him to attend battlefields while working for the Paris newspaper Gil Blas during the First Balkan War. He sent a letter directly to the Russolo “from the trenches of Adrianopolis,” as the recipient put it, containing a prose-poem called “Zang Tumb Tumb,” utilizing a style that Marinetti called “onomatopoetic artillery,” in which the rhythm and sound of words both real and imagined words imitated the rhythm and sounds of modern battle. You can hear Marinetti himself reciting “Zang Tumb Tumb” in 1913, as set to a Futurist film the following year, in the video below. It is powerful.

Russolo reprinted “Zang Tumb Tumb” in the contents of a letter of his own, a manifesto that did not title itself such, publicly published on March 11, 1913. Fawningly addressed to Pratella, “Great Futurist composer,” Russolo stated immediately that it was while attending a performance in Rome “of your revolutionary Futurist music” that “a new art came into my mind which only you can create, the logical consequence of your marvelous innovations.” Russolo called this new art The Art of Noises.

Pratella only wanted to rewrite musical composition; Russolo wanted to reinvent musical instrumentation. “Do you know of any sight more ridiculous than that of twenty men furiously bent on the redoubling the mewing of a violin?” he asked early on, presumably rhetorically, to demonstrate his argument.

Complaining that “musical sound is too limited in its qualitative variety of tones,” and how “this limited circle of pure sounds must be broken,” Russolo called for the “discarding (of) violins, pianos, double-basses and plaintive organs.” He invited a new categorization of musical noises, and proposed a new set of instruments to play them.

As his paintings had already indicated, Russolo was a true Futurist, someone “in love with the modern world,” to quote Jonathan Richman from six decades later. “It’s no good objecting that noises are exclusively loud and disagreeable to the ear,” he wrote in the Art of Noises, citing nature’s own abrasive sounds of, for example, thunder. “Every manifestation of our life is accompanied by noise.”

Determined to replicate these sounds with musical instruments, Russolo nonetheless insisted, and in bold type, that “the art of noise must not limit itself to imitative reproduction.” Rather, his new instruments would achieve their “most emotive power” through “combined noises.” Accordingly, Russolo duly laid out “6 families of noises of the Futurist orchestra which we will soon set in motion mechanically.” He then listed these families across six horizontal columns, each falling away into multiple components. Column 4, for example was headed by “Screeches,” underneath which were listed, each on a separate line, “Creaks,” “Rumbles,” “Buzzes,” “Crackles,” and “Scrapes.” (See below.)

It was a powerful and ultimately influential presentation – for with the Art of Noises, Russolo had laid out not just a manifesto, but in his assurance that “the practical difficulties in the construction of these instruments are not serious,” a means by which to act upon it. Accordingly, when Pratella, gainfully employed as a composer, proved resistant to the invitation to discard the old orchestras and build entirely new ones, Russolo set rapidly about constructing what he called his intonarumori himself.

It's important to note that Russolo was not alone in his pursuit of a new musical paradigm. Among many other moves away from the mainstream, the debut of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring took place in Paris just two months after the Art of Noises was published, causing a riot in the audience but ultimately shifting the musical compass.

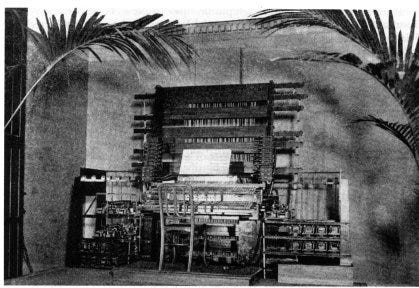

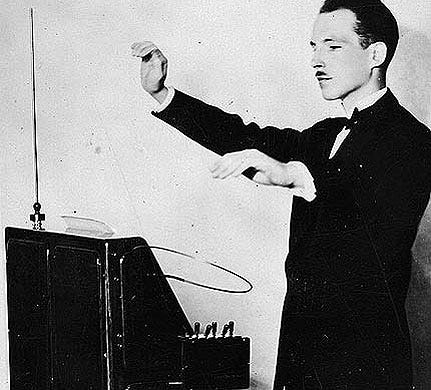

Nor was Russolo in pursuit of the first electric instrument, a race that had been taking place for years already, though not to my knowledge in Italy. And it’s worth a quick tangential detour… The first grand vision of an electrical instrument had hailed from the USA, where Bostonian lawyer Thaddeus Cahill adopted and adapted the new telegraph system for his Telharmonium, patented in 1897, which utilized ten switchboard panels to operate 2000 switches, but weighed some 200 tons, all of which were nonetheless transported down to New York City in 1906 for a concert at Carnegie Hall. On the other side of the world, the Russian Leon Theremin would come up with something considerably more compact in 1920, using a simple pair of antennas to sense the movement of the player’s hands, one of which controlled frequency, the other volume. The theremin is still in use today. The telharmonium? Um, not.

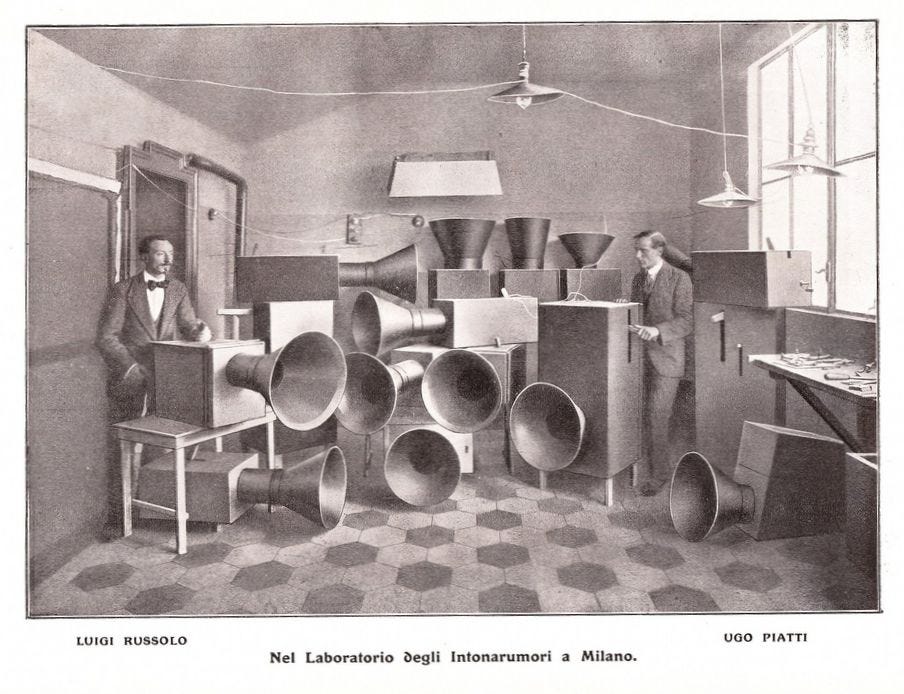

As for Russolo, his intonarumori were very much analogue: sound-producing machines “operated by handles and levers,” “designed to modify or ‘tune’ the pitch, rhythm, and amplification of a noise-sound” according to Poggi, and then placed inside boxes of various sizes, the better perhaps to preserve their mystery. The first of these, his realization of what the manifesto had categorized as a “burster,” and which he called the scoppiatore, was built within a month of the Art of Noises’ publication. Further intonarumori would soon be built to fulfil his other categories, and Russolo acquired the first of three patents for these instruments in early 1914. By this point, the sole existing photographs of him with his intonarumori had already been taken (see up top and bottom), as had the instruments’ only few unaccompanied recordings been made. You can hear those 110-year old artefacts on the first few tracks of the album below.

Interestingly, Russolo may not have been quite so Futuristic in his research as his vision suggested. The Italian composer and musician Luciano Chessa, Russolo’s most recent and seemingly his most thorough biographer, has posited in a separate essay that Russolo drew as primary influence for his manifesto and intonarumori upon Leonardo da Vinci, who was otherwise considered by Futurists as one of the passatisti. Stating that “Leonardo’s support for the infinite division of the semitone was a progenitor of Russolo’s enthusiasm for enarmonia (microtonality),” Chessa also notes “the rapidity with which (Russolo) constructed” his intonarumori “was due to his capitalizing on Leonardo’s research.” Reprinting a detailed illustration by da Vinci from somewhere between 1480-1518 demonstrates this point:

It appears that his work on restoration of the Last Supper had had an influence on the young Russolo that superseded subsequent Futurist attempts to bury the past princes of Italian art, as evidenced in Russolo’s last writing, from 1947, the year of his death, in which he praised the Last Supper as “pure spirit (which) lives outside even of its own material body,” and heaped similar reverence upon the Mona Lisa.

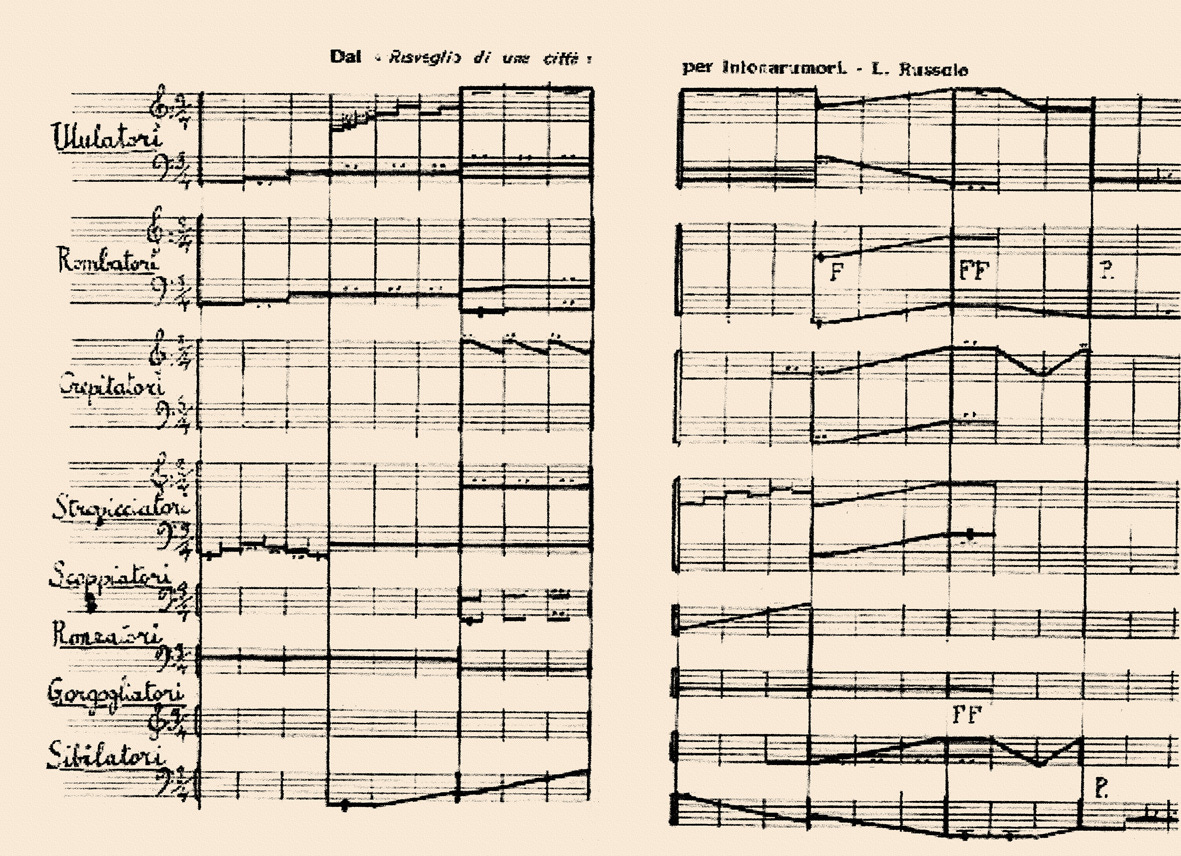

More evidence of Russolo’s relative formality comes with the sole remaining trace of what he intended to be a benchmark 1913-14 four-part suite of “noise spirals,” these being the opening seven measures/bars of a score for its first part, “The Awakening of the City.” Despite adding a rubber, a low hummer and a whistler to listed intonarumori, Russolo chose to use the familiar western treble and bass clefs with their five-line staves, though admittedly he did not seek much by tradition thereafter:

These opening measures/bars, combined with the sight and sound of his intonarumori, invited a similar response when presented at a formal unveiling concert in Milan in April 1914, as to that of The Rite of Spring in Paris eleven months earlier. One of two prominent reviewers in attendance, after observing that “the players” looked like “musical knife grinders,” noted that an initial “long, monotonous and indefinable sound” – presumably the slow glissando - produced jeers and shouts from the audience, for soon afterwards, “no one could hear a thing” as “the public was absolute in its intolerance.”

Nonetheless, Russolo stubbornly continued to conduct, reaching the third of his “noise spirals,” this one entitled “Conference of Cars and Airplanes,” before one attendee threatened to throw chairs onto the stage. This prompted Russolo’s Futurist comrades – Marinetti, Carra, Boccione and Mazza had all come to support – to physically assault the interloper; in the ensuing “free-for-all,” two of the Futurists were injured and Marinetti temporarily seized by the carabinieri. The melee continued outside, the Futurists followed by “a long train of passatisti” according to one of those reviewers, who noted with a wink in his tone, of what he called “an even livelier and noisier racket” than the so-called concert that had preceded it: “Russolo might have taken this cue for a marvelous symphony in the Futurist style”.

There is presented, within these reviews, the image of a rather forlorn Russolo attempting to prove merit as a serious Futurist artist, discovering instead that, as Gavin Williams wrote in an essay subtitled “Futurism and the Politics of Noise,” which reprints large sections of the two reviews, “Russolo’s noises were at the mercy of their interpreters”; the composer and constructor “could control neither the symbolic currency of noise nor the voice of the crowd”. Russolo was nonetheless invited to London to perform with his intonarumori for three nights at the Coliseum that June, where audiences were less inclined to physically riot, though the London Times still noted of what it sarcastically called the “noisicians” that “pathetic cries of ‘no more’ … greeted them from all the excited quarters of the auditorium.”

But this is always the way with the new. Audiences struggle to react positively to something they have not encountered previously, be it audio or visual, and elements of the Milan crowd in particular may have felt within their rights to bring additional noise to the event given Futurism’s history of purposeful provocations. Such ultimately low-grade battles were now taking place all across Europe just as more fatal high-grade ones were launching on an unprecedented scale: in September of 1914, as World War I broke out across Europe, a now-familiar cadre of Futurist leaders upended the Milan premiere of Puccini’s Fanciulla del West by unveiling an Italian flag, tearing up an Austrian one, and repeating their nationalist displays the following day in the city center, provoking street fights; the core group, including Russolo, were arrested and spent six nights in jail.

The Futurists’ overt Italian nationalism and pronounced celebration of war extended to personal engagement on the battlefield, and Russolo was among those who volunteered to serve. In 1917, he was seriously wounded in the head on Mount Grappa and spent two years recuperating in various hospitals. (Buccione was among those Futurists who did not come home from the War.) He resettled in Paris, the arts capital of Europe, and finally resumed performances with his intonarumori in 1921. The fact that one such concert in June of that year, at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, was invaded by participants in Futurism’s artistic successor movement, the Dadaists, might have frustrated Russolo, but should certainly not have upset Marinetti. The original 1909 manifesto had stated, after all, that “When we are forty, other younger and stronger men will probably throw us in the wastebasket like useless manuscripts—we want it to happen!” (Russolo was still only 36 in 1921.) Nonetheless, these Paris concerts proved influential with the likes of Ravel and Stravinsky, who was said to have considered including the intonarumori in his own music, something that Pratella did that same year before losing interest in his own Futurist visions, and his engagement with the movement (and to some extent music) along the way.

Still, Russolo was evidently working too far on the fringes of music to meet with commercial success, which might explain why the lone recording of his intonarumori performing actual compositions, a short “Corale” and “Seranata” from 1924, features them alongside regular orchestral instruments after all.

And while his paintings were undoubtedly distinctive, and much of his work from 1910-13 emblematic of Futurism philosophy, Russolo was unable to elevate it to another level; his 1926 painting Impressions of Bombing, Shrapnels and Grenades suggests that he was still suffering from what was surely a form of PTSD.

However, Russolo’s incapacitation during his recuperation did eliminate him from participation in the political process by which, led as every by the uber-nationalist and militaristic Marinetti, the Futurists helped formulate and populate the Fascist movement. Marinetti himself co-authored the Fascist Manifesto in 1919 and later fused his own Futurist Party into that of the National Fascist Party which, under Benito Mussolini (who Marinetti campaigned alongside), seized power in 1922 and formed an Alliance alongside Hitler that led to World War II.

This is what Al Gore, in a different context, calls “an inconvenient truth.” The same creative people who had fascinating visions of an artistic futurism, readily fell for the captive cult of personality of an ultimately fascist leader – the wealthy Marinetti – who led them not only into the trenches of WWI but in his own significant way, helped lead the planet towards a frightening embodiment of a Fascist vision, which resulted in a WWII that killed 60,000,000 people and ended with Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I state all this with obvious comparisons to the here and now, to the “cult of personality” presented by self-proclaimed leaders born into a wealth that allows them to engage in hostile politics of racial superiority and totalitarianism, corporatism, Imperialism, and Militarism (the common definitions of fascism per the Encyclopedia Britannica) – and yet who somehow succeed in bringing the masses along in support of the masses’ own undoing.

But back to the Futurists, whose engagement with the emerging fascism was always on the cards. In an article entitled “Rough Music, Futurism, and Postpunk Industrial Noise Bands,” published in 1987, Mary Russo and Daniel Warner write how “Russolo had been an inspired participant as futurist performance moved in and out of fascist scenarios; war and futurist aerial theater were born together” and how “early futurism and early fascism shared and exalted noise, especially the noise of violence”.

Yet most historians and academics, the media, and even us music-lovers, have somehow managed to separate Futurism from fascism over the course of the last half-century. Many of the papers I researched for this article of my own don’t even use that f-word, nor does this summary of a BBC podcast on Futurism that formed part of an ongoing Free Thinking series. And while the actual show in question did address the issue, it did so only marginally, preferring to present instead – literally, on a plate for the BBC’s food critics - recipes from 1932’s The Futurist Cookbook, written by Marinetti himself, full of purposefully provocative meals only some of which are edible. The Futurist Cookbook also sought to eliminate from the Futurist menu all traces of pasta - yes, in Italy - based on an assertion by Marinetti that pasta “makes people heavy, brutish… skeptical, slow, pessimistic.” I know a few gluten-free advocates who would agree.

If Marinetti can be excused his role in Fascism by BBC Radio’s intellectuals, it’s no surprise that Luigi Russolo has escaped almost completely unscathed. The same Russo and Warner who note above the close ties between fascism and futurism, state in their essay that Russolo “never witnessed the real effects of the fascist regime on Italian culture.” Not so. In his 2012 biography of Russolo, Chessa cites specific fascist-sponsored events Russolo participated in Italy in the late 1920s, and observed that Russolo’s “permanent return to Italy in 1933, as well as some of his subsequent writings, signal first acceptance of and then allegiance to the fascist regime”. In a more recent lecture, Chessa states that Russolo ultimately survived his latter years in Italy only because he received an Italian Government pension thanks to the personal intervention of Marinetti with Mussolini.

Perhaps there is a certain irony that all of Russolo’s self-created intonarumori were destroyed in World War II. All that survives physically of his musical vision is the few limited recordings, the scrap of composition, and a pair of photographs from 1913, the second of which you can see below.

Nonetheless, Russolo’s influence, while none quite so revolutionary as can seem upon the surface, is now widely recognized. A 1983 introduction to Russolo’s 1916 collection of essays, itself called The Art of Noises, praises Russolo’s writings for “the first expressions” of “the doctrines of musique concrète”. The composer John Cage cited Russolo’s importance in developing a new language for music in New York in the 1950s. And in case you thought I wasn’t going to mention it, producer Trevor Horn, he who commercialized the first (Fairlight) computer samplers with his work for Yes, Frankie Goes To Hollywood, and Buggles in the early 1980s, named his record label ZTT for Zang Tumb Tumb and his own musical project The Art of Noise. An article in Far Out magazine in 2020 goes so far as to state that “Luigi Russolo … allowed bands such as Einsturzende Neubauten, Sonic Youth or even the guitar solos of Rage Against the Machine’s Tom Morello to perform something recognised by many as art”.

And though the original instruments were lost in the battle against fascism, in the 21st Century Russolo’s intonarumori have been rebuilt several times, including for a 2002 concert of original material performed in Tokyo and later released as an album; a 2009 concert in San Francisco entitled “Music for 16 Futurist Noise Intoners,” conducted by Luciano Chessa (see below); an exhibition at the Museu Coleção Berardo in Lisbon in 2012 (see above); and a 2019 album entitled The Noise of Art: Works for Intonarumori, featuring Blixa Bargeld and Luciano Chessa among others.

At the end of the day, Luigi Russolo provides a truly fascinating case study of a multi-faceted artist whose influence remains apparent even though he fell victim to both his limitations and his over-reaching. He was also unable to rise above the political leanings of those he followed into a battle that proved as literal as it was metaphorical, with near-fatal results for the artist at the time, and at significant cost to humanity at large in the years that followed. What is a music fan-historian to do but to study our history, so as to only repeat the better parts of it...?

Fascinating stuff, Tony. I had a very superficial awareness/understanding of these folks and their movement - largely through their influence on Horn and ZTT - but this piece greatly expanded my knowledge on the subject. Thank you!

This is great . And all new to me. Thank you!