If the likes of Siri and Bixby were not Artificial intelligence, they would answer your question, “Define a cult artist” with the response: Bill Nelson. The musician, composer, singer, artist, and guitarist extraordinaire has been making music for over 50 years now, some of which has been commercially successful (most notably with his early 1970s band Be-Bop Deluxe), some of which has been critically acclaimed (including the post-Be-Bop band Bill Nelson’s Red Noise, about which I interviewed him below), and much of which has fallen under the radar, in part because Bill long ago turned his back on the demands of the major music industry and became one of the first post-punk-era examples of the musician as cottage industry.

Quite literally: Bill has spent decades working out of his farmhouse in West Yorkshire, taking control of all aspects of his music, which has run the gamut over these decades from art rock to ambient, with many points between. If you would like to read more about him, I recommend this bio at AllMusic, and if you would then like to read more by him, I can recommend his second Diary of a Hyper-Dreamer, as published by Mark Hodkinson’s independent imprint Pomona, though Bill proves somewhat excruciating in his perfectionism, which probably comes as no surprise to his legions of fans!1 Volume 1 is entirely sold out and I have never seen a copy.

At the time of the interview, in early 1979, Bill Nelson had split Be-Bop Deluxe and formed a new group. The clip above is of Bill Nelson’s Red Noise, featuring Steve Peer on drums, performing three songs on the Old Grey Whistle Test, as introduced by the recently, dearly departed Anne Nightingale. Unfortunately, her intro and outro are not her finest moments.

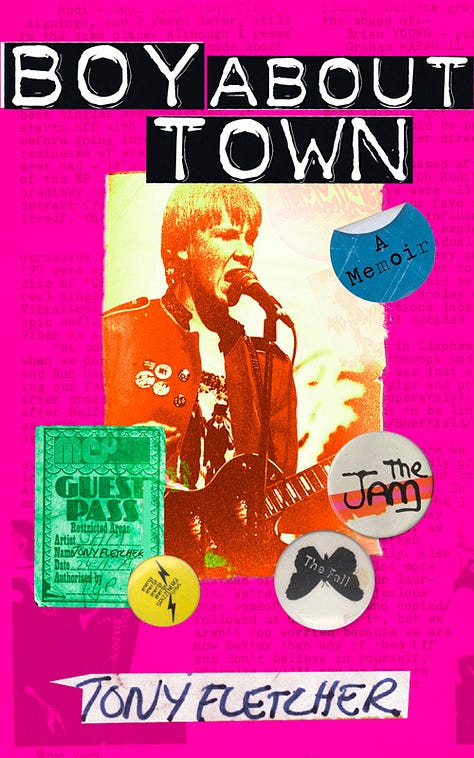

By way of actual introduction to this essentially unedited interview drawn from the typed manuscript I have kept in meticulous condition for 45 years now, I offer you two introductions. One is from Boy About Town, my early teen memoir published in 2013, in which I describe my love for Nelson’s 1970s rock band Be-Bop Deluxe - their 1976 LP Sunburst Finish will always be up there as one of my favorite albums, certainly of that era - and describes the process by which I conducted the interview below.

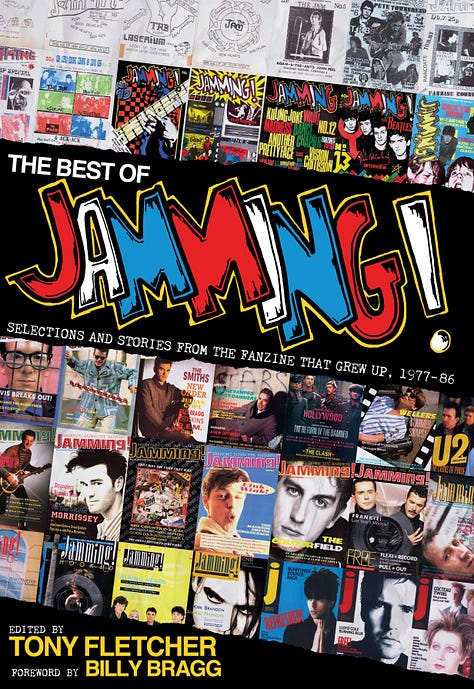

The other intro is from one of Bill’s band members at the time, the Red Noise tour drummer Steve Peer, who befriended me that day in early 1979, kept up a pen-pal relationship for decades, and has since played host to me a couple of times up in Maine, where he now lives. I originally asked Steve for a quick blurb to accompany this interview in The Best of Jamming!: Selections & Stories from the Fanzine that Grew Up 1977-86, but he wrote back a small essay. I assured him that one day we’d have opportunity to use it. That day is here.

First, from Boy About Town:

“I’d bought the Be-Bop Deluxe LP Sunburst Finish after seeing them at the Great British Music Festival way back in early 1976, and still loved it. (On their final album, Drastic Plastic, however, they tried to jump the new wave bandwagon, and lost all sense of place and purpose in the process; Bill Nelson appeared to admit as much by announcing their break up soon after.) So when Bill Nelson announced that his new band Red Noise would be releasing an LP and going on tour, I decided to go after him for an interview.

Nelson didn’t have a fan club, didn’t run a book store, didn’t send out newsletters. I had no choice but to approach him the official way. I called the EMI switchboard a few times and was eventually given the number of his “publicist,” Tony Brainsby. (And there was me thinking that publicity was part of the record company’s job.) I called Brainsby’s office and found myself on the phone with a girl called Magenta DeVine. The conversation was productive, and a couple of days later I went to their office in central London and hand delivered the last two issues of Jamming. There were gold and platinum discs lining the walls, and there were conference rooms and sofa chairs. I was impressed. I had been spending all my time recently in record store basements and rooms above pubs, hanging amidst the backstage graffiti at the Marquee or rehearsing alongside the political slogans at the Brixton Advice Centre; I had almost stopped considering how much money there was in the music business for those who knew how to make it.

A few days later Magenta called to schedule me an interview during Nelson’s tour rehearsals – which were conveniently taking place inside the old Astoria cinema opposite the Brixton police station. But more important than location was the matter of acceptance; this was the first time anybody working with the major record labels had recognized Jamming as some sort of proper publication.

And then, a few days before the interview, I got another late afternoon call from Magenta. (All my weekday phone calls were late afternoon; I had no idea how often the phone rang when I was at school.) She told me, with brisk sincerity, that she was cancelling it. There were too many people wanted too much of Bill’s time, and the band leader himself had asked her to postpone my interview. “I’m sorry,” she said when I protested, “but Bill’s priority right now is to get his shit together.”

Get his shit together? That was the kind of thing an American rock star might have said - before punk came along. It certainly wasn’t the kind of thing I imagined Bill Nelson saying to anyone.

So I turned up for the interview anyway. That following Saturday, earlier than originally planned, I went to the old Brixton Astoria and I waited for Nelson outside the stage door. When he arrived, in a chauffeur-driven car, I approached him and explained my situation, and just as I thought, he knew nothing about any of it. He thanked me for my enthusiasm and persistence, invited me to come in with him and told me I was welcome to stick around all day. It was only when we were an hour into the interview itself that he suggested he really ought to get on with rehearsing his new band for his big tour. He never once uttered the term “getting my shit together.””

And now, from Steve Peer.

“Bill Nelson is one of the finest gentlemen ever and one of the most judicious and tactful guitar players of all time.

It was both unexpected and exciting to meet Bill as he strolled on the Asbury Park boardwalk prior to the Be Bop Deluxe show at Convention Hall in April 1978. He was one of my new musical heroes and I was happy for an opportunity to share a cassette demo tape of my New Jersey band, TV Toy, with him.

Though I was not anticipating this encounter, I had been prepared to make contact with Bill or one of his bandmates or crew. My intent was to convince Bill to produce the TV Toy album that was the band’s next logical step. The 3-song demo was an accurate representation of our musical and creative prowess and '70's hard rock influence.

A few weeks later I got a call from Bill's management company and scheduled a meeting with his personal manager. Clearly Arnakata Management, Ltd. was interested in TV Toy. Instead Michael Dolan told me that Be Bop Deluxe were no longer a band and that Bill had recorded demos for a "solo" album and new players were needed to record the album, and would I be interested? Not what I had expected, but a wonderful and flattering offer nonetheless.

Torn between loyalties, and deeply affected by the fact that this offer did not include them, my band mates in TV Toy decided regardless that it would be a good business move to accept Bill's offer. Dolan was clear from the beginning that this was going to be a band of hired hands, and the first of many band line-ups that Bill had in mind. Knowing that, I did not feel I was leaving my band behind, but instead that I was going to be networking in the UK, where TV Toy suspected appreciation and success may lie.

In August 1978 road manager Paul Bailey picked me up at Heathrow Airport and took me to Trader Vic's where I met bass player, Rick Ford, and Be-Bop keyboardist, Andy Clark, the current members of Red Noise.

Next stop? Wakefield. In an early 20th century town hall outside the city, the band's gear was all neatly arranged by roadie, Peter Carr, and Bill's personal tech, Stuart Monks. Rehearsal commenced and once we stopped staring at each other wondering what to do, Bill suggested we loosen up with some blues, and he launched into "Red House." It was clear he had a knack for the blues and like many players, had done his Hendrix homework. Relaxed and wound up at the same time I blurted out "Hey, can we play "Possession" or "New Precision," assuming that at least Bill and Andy knew the tunes from the final Be Bop Deluxe album, ‘Drastic Plastic’. Fortunately Rick and Ian, Bill's brother, knew enough of each tune to join in the fun and off we went.

I thought the rehearsals were going well, but apparently not. I was sent back to America with little explanation. Feeling confused, I got back to business in New Jersey with the memories of my summer in Yorkshire still ringing large.

A month or so later Michael Dolan got back in touch asking if I could do the Bill Nelson's Red Noise UK tour. Suddenly I find myself back in London, with a paid flat, a weekly salary and attending rehearsals taking place in a closet somewhere in the city. Of course, I am wondering why I am back in the band. Where is Dave Mattacks who did lots of drumming on the 'Sound On Sound' album?

A clear explanation was not ever offered, but after a few rehearsals I could see why most drummers at the time would have turned down the job. The album was energetic, weird, angular and progressive in nature. The live band was all that and more, extremely frenetic and not a space or breath could be afforded performing the album. At the end of the 40-minute concert set one could lose several pounds and a ventilator would have been more welcomed than a frosty beer. I concluded ultimately that Dave was busy and not able to tour, whereas I was available, easy to get along with (I felt), and willing to wear the wool uniform Bill had tailored for each band member.

As my friendship grew with Rick and Andy, they did say that my playing was a bit... unpredictable, and not always "in the pocket." This tendency, they explained, makes recording very difficult for other players. I remind myself of their words every time I begin a recording session these days, and it remains good advice. Meantime, live on stage, I continue to channel Keith Moon and make it as difficult as possible for other players.

Once Red Noise had the arrangements and the stamina to perform the set, it was time to rehearse the band with lights and sound and assemble all the components of the show.

We secured an old cinema in Brixton, which is better known these days as Brixton Academy. The dank theatre was dripping with water, hovered around 40 degrees Fahrenheit, and there was the reasonable fear that the proscenium arch would give way at any moment. It was here that I met Tony Fletcher, the 14 year old teen lurking at the back of the theater resembling one of Fagin's lost lads in the dimly lit cavern. I may not have stopped mid song, but I wasn't going to let this kid stand there. I knew all too well what it was like waiting and hoping to meet the band after a show, and I wasn’t going to leave him looking and feeling lost. Tony had found his way to this abandoned theater, and I was going to assist him in completing his mission, whatever that may have been.

Come to find out Tony had arranged, properly through management, to interview Bill, but it had been cancelled on him so abruptly that he decided to show up anyway. Due to Bill's friendly and easy going nature Tony got his interview. I just re-read it before writing this, and again I can feel Tony's determined spirit in his direct questioning, and I remain in awe of his background knowledge, and his willingness and ability to do research and dig deep.

In reading the interview I was reminded of how Bill often came off as somewhat cool and distant, when he was actually quiet, coupled with an aloof shyness. I often wondered, even back in 1978, how these attributes, or misperception of attributes, may have limited his career. Also in the interview there is a subtle antagonistic tone Bill used when referring to his contemporaries. I know that he took lots of unwarranted, inaccurate criticism and his share of snide comments, and I suppose, at times, he not only felt misunderstood, but also unjustifiably knocked around and mistreated. Not convinced that pushing back at the tormentors was, or ever is, a good strategy, I can’t help thinking that some bridges may have been burned.

During the Red Noise days, Bill had an aversion to the "guitar hero" and the guitar solo, and for several years, post-Red Noise, perhaps the guitar altogether.

All of this being said, I have fond memories of spending a few nights at Bill's Yorkshire villa, he and I catching the midnight movie spectacle of "Rocky Horror Picture Show" in London, adding the tune "Possession" to the set list at my request and letting me contribute the Ramones-like chant and throttling drums at the end of "Art, Empire, Industry," for teaching me the art of hand-picking every luscious note, and how to construct quirky and efficient pop music.

Epilogue: After Red Noise I returned to a New Jersey rock'n'roll scene that was still in the shadow of New York City, and which I wanted to tell the world about. Yes, Jersey was home to Frank Sinatra, The Four Seasons, Whitney Houston, and The E Street Band; however, now it was The Feelies, TV Toy, Misfits and The Sugar Hill Gang. Having struck up a pen-pal relationship after our meeting that day at the Academy, Tony Fletcher went on to feature "The New Jersey Scene" in Jamming (no. 9), later in 1979, sharing the exciting subterranean music happenings from the suburbs of the Garden State with the rest of the world.”

The interview that follows runs almost 5000 words and is for paid subscribers. Subscriptions start at $5 a month, or $50 for the whole year, and as well as granting access to exclusive features such as this, also provide you with access to the Crossed Channels podcast, and the full Wordsmith archives.

As a further tease, I’ll start with this pull quote.