JUST BACKDATED: Seven Years In The Seventies

A memoir by Chris Charlesworth details the bygone 1970's rock world from a truly unique perspective.

Chris Charlesworth was my first book editor, and we became good friends along the way. I published two extracts from Just Backdated upon its publication because it seemed a good way to help publicize his deeply personal endeavor, and if you’ve read them, you’ll know they were excellent. However, Chris and I are both straight shooters, and if I thought his memoir as a whole was not worthy of further write-up, believe me, I would have left it there.

Indeed, this review is late to the game; Just Backdated was published several months ago. But although I’m hardly a slow reader, I’m an adulterous one; I keep five or six books on the go at any one time, am constantly being gifted or buying more, and therefore struggle to finish any, a process not helped by the fact that I like to read every word. It’s a post-graduation and midsummer resolution now that I am clawing some time back in my life, that as I finish a music book, I will review it.

On the surface, the notion of a Melody Maker journalist writing about his time at the paper in the 1970s is an unappealing one. While Melody Maker was the commercial heavy-hitter for much of the decade, outselling NME, Sounds, Record Mirror and anything else that came along in the music paper stakes, it did so by aligning itself with the mainstream rock music of the era, a lucrative and mutually ripe apple cart that it rarely sought to upset. Further, it had the feel of a broadsheet newspaper more than it did a magazine (front covers were as likely to announce a star group’s impending tour as an exclusive in-depth interview), and the inside features sought to inform more than they did to opine.

As such, when punk hit, it was the NME, under editor Nick Logan, which was better poised to understand that the surface nihilism of the musical subculture nonetheless represented an opportunity for fearless journalism, and recruited the necessary young writers to pen it. Sounds never rose to the same level of prose, but it had the street cred to be a worthy challenger, especially when the NME’s writers overdid their pretentiousness and alienated those readers without a PhD in Thesaurus. Melody Maker, by comparison, stuck largely to its guns – the big guns, the people that still sold records by the boatload and filled the arenas - and while that kept its head above water, as did its dominance of the classified ads market (which was how bands recruited members back in day), the paper got left behind in the 80’s and was finally incorporated into its IPC rival, the NME, in January 2001.

But before punk hit and changed everything, Melody Maker was it. And it’s a measure of its it-ness that by the early 1970s, it could afford to assign a writer to the States, where a weekly domestic music paper market did not exist – other than the reverence held for the British ones that occasionally found their way over to select newsstands on an almost mythical (and apparently highly belated) basis. And when I say that Melody Maker assigned a Stateside writer, I don’t mean that it employed a freelancer or two in the States, or even that it put an expat Brit on a retainer.

Rather, the paper paid for one of its London-based staffers to relocate to the USA, covered their accommodation costs along with some other living expenses, and then paid that staff member their going wage. The clout that came with the position as the only full-time American-based employee of any British weekly music paper, but also the British music weekly paper, ensured that said staffer quickly found himself (and it was an almost entirely male-dominated medium/media back then) cheerfully up to his neck in promotional music, free concert tickets, expense account lunches, dinners and parties, and access all areas to the biggest stars of the decade, sometimes for interviews, often just for the lig.

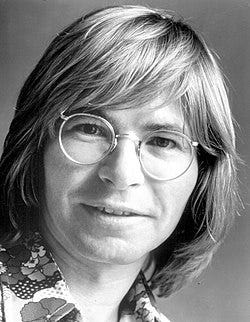

It was the life of Riley, a life only ever truly experienced to the full by one man: Chris Charlesworth, whose tenure as MM’s US editor, first in LA but primarily in New York City, was doubled beyond the expected sequestration, mounting to almost four years during the very pinnacle of the free-flowing rock era: 1973-77. In short, only one person could have written Just Backdated, and that one person has now done so. Fortunately, it’s a riveting read.

Tony Fletcher, Wordsmith posts twice a week, every week. Subscribe to get the posts in your Inbox. Upgrade to a paid subscription to receive the exclusive interview manuscript posts, unlock the archives, and to hear the Crossed Channels podcast co-hosted with .

Chris Charlesworth’s early journey, from Skipton to London, is one of Yorkshire-bred fortitude and fortune. Born in 1947 “into a comfortable, middle-class, loving family,” he was the perfect age to fall for early rock’n’roll, and even better placed to witness the birth period of Beatlemania in Bradford at the age of 16, at almost the exact same point that he realized his future lay in journalism. With the necessary qualifications, he joined the staff of the local paper as a cub reporter, where his enthusiasm for rock ’n’ roll ensured that he was soon able to add a Music Column to his regular reports from the Magistrate’s Court.

Seizing an opportunity to move south when the paper’s owners announced a new evening paper was being launched in Slough – that west London outpost known to viewers of The Office as a cultural vacuum – Chris nonetheless parlayed the suburban location into a couple of swinging romances and a mind-expanding, life-altering experience watching The Who at Plumpton Racecourse in the summer of 1969. Later that year, his mother took her own life to put herself out of the painful misery of a debilitating back condition; metaphorically though far from literally, Chris never went home again. An unsuccessful interview for the Melody Maker, in which he apparently “prattled on” as Yorkshiremen are prone to do (takes one to know one!), nonetheless led to a call from new editor Ray Coleman a couple of months later. In early 1970, he was hired full-time.

The author’s first days at MM are recounted with a nostalgic wide-eyed wonder. MM was an IPC flagship, located on Fleet Street, selling almost 200,000 copies a week, every week, and while its staff included some who appeared to be holdovers from its 1926 launch, a recent mass defection to start the rival Sounds saw Charlesworth work alongside people like Chris Welch, Richard Williams, photographer Barrie Wentzell and others to re-establish the veteran paper’s superiority. Charlesworth soon learned that reporting on musicians meant hanging out with them, and knowing exactly how much of the hang to write up and how much to leave to personal memory (and a future memoir!), proved a job to which his amiable personality, dapper dress sense, musical enthusiasm and business nous was perfectly suited. Chris soon became the paper’s News Editor, and by late 1973, was offered the gig as MM’s “Man In The US.” He had found his calling – and though we are about a quarter of the way into Just Backdated by the time this transition takes place, during which he has had more plane journeys to the States already courtesy of record company largesse than most people manage in a lifetime, his memoir finally finds its stride.

What follows is an astonishing roll call of interviews, concerts, intimate encounters and occasional arguments with the higher echelons of the American music industry at a time it was rife with cash, cocaine, attendant self-confidence and what would ultimately prove a misguided sense of counter-cultural victory.

Chris found himself close to managers like Chas Chandler (Jimi Hendrix, Slade), Pat Meehan (Black Sabbath) and Peter Rudge (The Who, the Rolling Stones), all of them old-school characters capable of providing rock star-level anecdotes. A favorable early review of Elton John led to a solid relationship that included playing table tennis with the singer att his English estate and years later, a phone call from a staffer at a New York press luncheon where Chris’s no-show worried the superstar that “I didn’t like him anymore!” (the author was on his Thursday morning deadline). He was fortunate enough to see Bruce Springsteen two nights in a row in 1974, an epiphany he writes about and which I previously published below:

And yet these are but minor detours in a journey that drew me to reach some greater conclusions. These I summarize as follows:

1) The Who were the greatest.

Chris was fortunate to witness surely the best live band that ever rocked the 70s, at the peak of their voluminous powers, and frequently so; of this I am more jealous than anything else in the book. He was, arguably, even more fortunate that Keith Moon called him at the London office of Melody Maker after the third of those live encounters, the first he reviewed for the paper, to thank the new employee for the kind words and to suggest a drink at the Speakeasy one evening. This was quickly elevated into a shared limo with the drummer to a Who concert at the Hammersmith Palais and a backstage introduction to the other three members - with whom he would soon be on similar first-name and occasional drinking terms.

And yet this series of events, almost impossible to imagine occurring in 2025, encapsulates the band whose everyman appeal never wavered; almost alone of the era’s rock stars, they could and would pick up their own phones, put in their own calls, hang with their fans, engage in public arguments on and off stage, act like drunken hooligans much of the time, and still come off like the uniquely improvisational yet anthemic rock Gods that they were whenever they took to the stage. Just Backdated is, of course, a line from The Who’s “Substitute,” a song that has never lost its power to amaze me, and by the tone of his continued admiration, Chris neither. (Excerpt below from one of Chris’s hangs with Keith in the US.)

2) Slade were the loudest.

Charlesworth’s admiration for The Who as a live band appears challenged only by the Wolverhampton quartet whose rise to chart-topping teenybop status in the early 1970s was never apparently sacrificed at the altar of volume. As a fan of those number 1 singles, indeed as someone who still owns his original copies, I can only lament that I never fully registered their commensurate credibility (hey, I was 10 at the time!) and that the only occasion I saw them live was at that horrendous Great British Music Festival at London’s Olympia in November 1978, where their status as “special guests” nonetheless saw them rendered support to The Jam and the Pirates on a bill that also included Generation X and was subject to skinhead violence. I loved recording the Slade Inflamed episode of Crossed Channels recently and now have further reason to envy Chris his gig diaries and personal relationships of the 1970s - though I doubt that even at my beer monster peak I could have kept up with the band’s seemingly ceaseless refueling sessions.

3) Led Zeppelin were the worst.

This is not necessarily a musical observation on my part or Chris’s – 10,000,000 arena rock fans can’t be wrong etc. - but Charlesworth’s insider accounts of their on-tour behavior confirms all the rumors and reports you’ve read elsewhere. With the exception of Robert Plant, they are best likened to Vikings set loose in our native Yorkshire a solid thousand years ago, raping, rampaging and pillaging as they went and somehow imposing their authority further in our own evident masochism for more of the same.

Chris saw this all first-hand from his journeys aboard their private plane. During one, a blind drunk John Bonham attempted to rape a stewardess, an incident Charlesworth was sternly warned not to report; during another, he was invited into a private room where manager Peter Grant offered him a sniff from a mountain of cocaine and then told him to write favorably about the show he had just seen. Conflict of interest? More like an offer you couldn’t refuse. There are worse instances of Grant’s obnoxious and intimidating management style, enacted on less influential people, none of which Chris appeared to encounter with any other act of the era, large, small, legendary or not. Curiously, Zep were simultaneously thin-skinned when it came to bad press, suggesting that violence or the mere threat of it is often a sign of the bully’s insecurity.

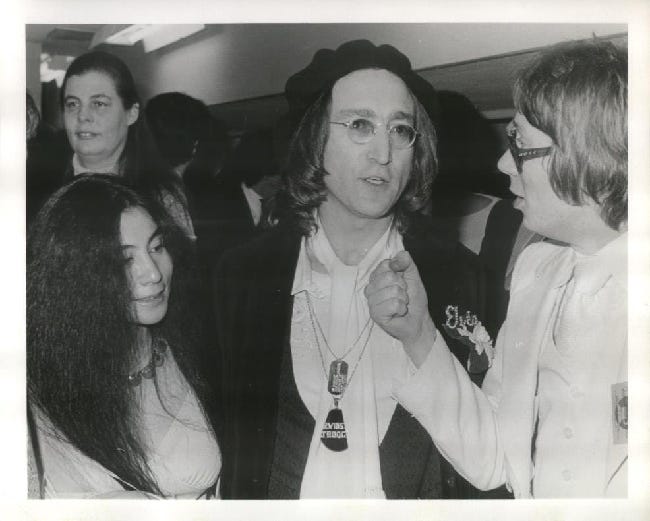

4) John Lennon was a beautiful human being.

Chris’s stint in LA coincided with John Lennon’s long lost “weekend” there, during which time he was able to secure an interview for Melody Maker in similar circumstances to how I landed my own Beatle interview a decade later. Back in NY (where Chris himself then spent the rest of his 40 months), Lennon recorded music, raised a family, and engaged in a now celebrated fight to acquire an American green card (i.e., permanent residency), despite the US Government’s apparent equal determination that he was a threat to public security. Charlesworth, his life inexorably altered by seeing The Beatles in Bradford as a teen, developed a friendship with his New York neighbor, in which “Johnny Beatle” would call the writer upon request by cable.

These two British expats shared a deep love for New York City, one I share with them both in turn, and yet it was New York’s very openness, that which Lennon so loved about the place, that led to his murder outside the Dakota in December 1980. Charlesworth, like myself, like anyone else who lives in New York and witnessed the good, the bad and the ugly – but mostly the great - struggles to reconcile it to this day, just as he does his access to the man he understates as “among the best-loved rock stars in the world.” Mystified, humbled and still in awe after all these years, he concludes: “I suppose he must have liked me. I have no idea why.”

5) Peter Tosh talked sense…

…albeit through a cloud of sinsemilla in an interview that reveals the fault-lines of the British music papers’ coverage. Chris’s stories are amazing, but they are almost exclusively of white musicians. The black artists who dominated much of the charts during the 1970s barely get a look-in from Melody Maker. Peter Tosh proves an exception, due to the Wailers’ commercial crossover and, in a scene I can well picture, Chris gets a walloping contact high in the process interviewing the now solo founding member of Bob Marley’s trio, suffering the additional delayed reaction that comes from attempting to interview someone in what suddenly reveals itself as a different language. (I recall a similar experience with Sly & Robbie in a NY record company office, minus the cloud of ganja on that occasion.) Charlesworth’s faithful reprinting of Tosh’s explanation for the Wailers’ break-up is presented as if it still requires translation (“Make of that what you will”) but it makes perfectly good sense to me.

6) Drugs came free. Sex came even freer.

Hey, it was the 1970s. The cocaine hangover had yet to kick in, and though marijuana was illegal, it seems like everyone did it in New York without much fear of being busted. Chris is honest about his experiences with these drugs and more - though at the end of each long day and night, he was frequently to be found at the Washington Square industry hang-out Ashley’s where, much like his mates in The Who and Slade, he was most comfortable as a good old British social boozer.

Charlesworth is even more open about his experiences with the ladies during this period. Sex, he writes somewhere, was considered a dating activity seemingly on par with playing a board game or watching a television show; for all the hook-ups, there were very few hang-ups, and almost no regrets. At one point, Charlesworth appeared to have a girl in every American capital, and writes with evident pride – and nostalgia - at occasionally sharing a bed with more than one partner. By the time I showed up in New York City to enjoy my own minor life of Riley as a well-situated Brit media man, it was almost exactly a decade after Chris returned home, the AIDS epidemic had hit hard alongside the equally dangerous (and murderous) crack cocaine epidemic, and hopping into bed with someone you had met two hours earlier was not to be recommended and in turn, rarely invited.

Still, you can only play with the cards you are dealt, and perhaps the most enjoyable anecdote in the book is the occasion on which Chris effectively stares down Steven Tyler over early-morning coffee at the apartment of a mutual romantic interest: the writer has just spent the night there, the Aerosmith star has shown up fresh from the studio expecting to spend a Saturday morning likewise. Tyler blinks first and departs. The girl thanks our author for not flinching. Score one for the journos over the rock stars!

7) John Denver nailed it.

To be clear, Just Backdated is not an award-challenging memoir on the lines of Fever Pitch, Lost In Music or Angela’s Ashes. It does not reveal the meaning of life and death, and there is no singular paragraph that rises to the level of a Lester Bangs or Tom Wolfe or, because we should name a Brit, Tony Parsons at his best. Chris’s strengths of character-driven writing are self-evident throughout the book, which is chronological, factual, faithfully and fondly recorded, and which draws extensively from Chris’s “diaries” – i.e. the archived pages of his Melody Maker contributions.

Though much of Just Backdated is about rock stars and stardom, by the time of the author’s recall to London in the spring of 1977, an event precipitated by the collapse of the pound against the dollar, he was a frequent attendee at CBGB’s, Max’s Kansas City and Club 82, and had even been invited to manage the earliest incarnation of Blondie, having given Debbie Harry her first write-up. (Turning it down appears to be his one regret; he made the right decision for where he was at the time.) Finding himself back in London was bound to be a comedown, which might be why he barely notes what came next, though I would argue that his second act – as book editor - was as important as the first.

Yet for all Just Backdated’s carefully chronicled access, all the anecdotes, all the occasionally sordid details and extensive enthusiasm, it is an entirely unexpected source of simple musical pleasures who provides the best quote in the book. It comes from the man he describes “an all-American Mr. Nice Guy in check shirts and dungarees,” one of the biggest stars of the era and yet one of the least acclaimed or/and offensive, John Denver. It was delivered during the course of a two-hour phone interview, it speaks to that same sense of fortitude and fortune that allowed Chris Charlesworth his unprecedented and entirely unique career opportunity, and that might explain why the author quotes it so extensively. Though I am only highlighting but part of it, it demonstrates that in the midst of an era in which ego and arrogance seemingly knew no bounds, some people recognized their place in the world after all.

“What success is to me is when an individual finds that thing that fulfils himself, when he finds that thing that completes him and when, in doing it, he finds a way to service his fellow man. It doesn’t make any difference whether you are a ditch-digger or a librarian or someone who works at the filling station or the President of the United States or whatever, if you are doing what you want to do, and in some way, bringing value to the life of others, then you’re a successful human being.”

As Chris notes himself, there is nothing much to say but: Amen. And, perhaps, to quote song title by his beloved Slade, Thanks for the memories.

Chris Charlesworth has been penning the Just Backdated blog since 2013.

Thanks for this, Tony, and sorry to only catch the post now.

In my limited correspondence with Chris, he's been unfailingly kind and responsive and I always look forward to a new blog entry from him.

In '22, Chris did me the great honor of publishing my review of The Who's return to Cincinnati on Just Backdated without a single edit. I'll always be grateful for that bit of charity and encouragement.

And, he's humble, too, folks: I once complimented Chris on what was a foundational read for me, his 1984 bio of Pete called "Townshend: A Career Biography," particularly memorable for its opening tee shot line. "Learning to play guitar hurts like hell," Chris wrote then, followed with a can't-be-a-yard-from-the-truth depiction of a young PT tossing his first guitar down after its strings and frets had gouged his flesh, something every guitarist has suffered at least once.

Chris thanked me for remembering it, but quickly cast shade on his own work. I believe he said he regretted some parts of the book as rushed, and wished he had timed the writing of that bio differently. Modesty is among the best of qualities, but I got the feeling Chris was truly and carefully reflective of his writing. That should clue his readers that he's always looking for a better phrase or a clearer perspective. And that's the only kind of writer I want to follow consistently. It reminds me of that West Wing episode where the top writers in the Bartlett administration pour over their draft of a birthday greeting message, because they "really want to nail it."

Anyway, kicking myself for having not his memoir already, so grateful for the reminder.

He covered a lot of stuff, and I wasn't interested in the big names as I already knew I found them dull. I was at school during most of his time there and had started taking the music papers a little more seriously. It was reading Chris' American coverage, far more interesting than anything anyone was writing in Britain, that made the Maker my favourite paper. That in turn ensured it was the paper I wanted to write for. Weird to think I also wrote a book for him, although I guess Omnibus was the only real player in the game.