London Calling New York New York

A new book by Peter Silverton makes unlikely bedfellows of two anthemic songs.

It is, for sure, a fascinating and theoretically winning concept for a music book. Take two anthemic songs about two major cities to which the author has a connection, two songs recorded and released at almost exactly the same time, and weave their individual narratives into a cohesive and compelling manuscript. When those cities are London and New York, among the most musically influential and traveled of all international pairings, the concept feels like a slam dunk, a home run, or, to even out the sporting metaphors, a shot on open goal from two yards out.

But when the two songs in question are “London Calling” by The Clash and “Theme From New York New York” by Frank Sinatra, the premise invites pause for consideration - to fact-check even. These two songs were recorded during the same period? They were hits at the same time? Shorely, shome mishtake?

Such was the task that Pete Silverton set himself in the final years of his life. The author, born in 1952 (outside London, but he considered himself a “Big Smoke” citizen ever since arriving aboard a Number 73 bus six weeks later), passed away from a terminal illness in May of 2023, a few months after completing the manuscript to this book. With that in mind, it’s unsurprising that London Calling New York New York is not just about the songs in question, nor what these songs reveal(ed) of the cities they name themselves for, but also about what a book tracing this kind of narrative can reveal about the author. Subjects tackled along the way include “nostalgia, mythmaking, family, crime, war, art, infidelity and propaganda,” according to his family’s posthumous introduction. Or, to quote from among the blurbs on the back cover: London Calling New York New York is “equal parts music biography, personal memoir, autoethnography and psychogeography.”

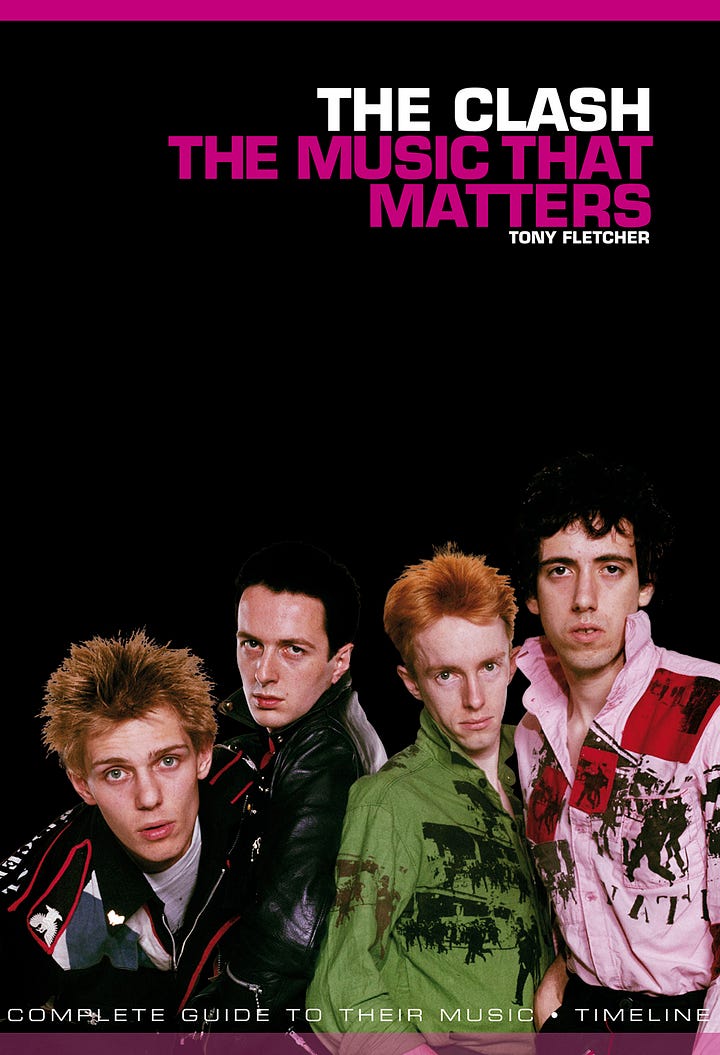

Disclaimer: I wrote that particular blurb. I was asked to pen one by the book’s American publisher, Ira Robbins of Trouser Press, a long-time acquaintance who reached out to me knowing full well that I lived much of my life in the two cities of the book’s title. [He was interviewed by Tamara Palmer on her Substack, about this very book, here.] Indeed, while I share the blurb credits with highly esteemed company – Chris Salewicz, Don Letts, and Lenny Kaye – I am the only one to have claimed both cities as a permanent home, to have citizenship to both their countries. Additionally, I wrote a book about The Clash and another about the music of New York City. I might have felt offended if not asked.

I was not, however, acquainted with the author. Never met him. Never recall exchanging correspondence with him. In fact, about the only time the punk-era Sounds journalist really crossed my radar was when he wrote a highly negative on-the-road cover story about The Jam, shortly before I interviewed Paul Weller in the summer of 1978, when I was but a 14-year-old schoolboy whose voice had yet to break, and Silverton, judging by the book’s lone photograph of him from that year, was 25 and auditioning as a stand-in for The Ramones. I raised the issue of the Sounds interview that day at RAK Studio as Weller was putting the finishing touches to All Mod Cons, and his response was the most emphatic of the day. Silverton, he said, was “a right prat” who, on the road with the band for a single show, “spent the whole night trying score some speed.” For good measure, he added of Silverton that “he’s just full of shit” and in case he had not yet been clear on the matter, “was a cunt.”

What was not mentioned was that Silverton was close friends with Joe Strummer, and firmly aligned with The Clash camp. There was no love lost between these two groups: The Jam had been thrown off The Clash’s White Riot tour in 1977, and a couple of months before my interview, The Clash released the single “(White Man) In Hammersmith Palais” in which Strummer took a shot at the new groups who “got Burton suits,” following with the immortal line, “huh, you think it’s funny, turning rebellion into money.” There were no prizes awarded for guessing his target.

For the record, I rate “(White Man) In Hammersmith Palais” as one of the greatest singles of all time. While not necessarily a better London anthem than “London Calling,” it’s the more visionary recording, “the missing link between black music and white noise” as Lester Bangs so perfectly described it. But it’s “London Calling” that trailed the double album of the same name at the end of the1970s (or the beginning of the 1980s if you lived in the States), that had the stompingly simple riff that American rock radio could embrace, the very Dylanesque apocalyptic worldview, and which repeated its title at the start of every verse, rather than, as with “(White Man) In Hammersmith Palais” waiting until the very last couplet even to mention it.

“London Calling” also had a somewhat iconic video to promote itself with, though in Silverton’s telling, largely according to director Don Letts’ own memory, the rain-swept film was as much a product of poor planning and inexperience than plot. But such are the circumstances on which legends are built. The Clash didn’t even want “London Calling” released as a single, and had to be talked into letting it share double A-side status with their cover of Willie Williams’ reggae song “Armagideon Time,” with the Blockheads’ Mikey Gallagher on organ. Ah, rock bands, as Silverton might well have written.

Silverton’s premise that “London Calling” is the London anthem is one he excuses, without ever quite saying as much, by his proximity to The Clash, having formed his friendship with the erstwhile Joseph Mellor back in the late 1960s; indeed, his introduction to Ira Robbins came by sending a request to cover Strummer’s pre-Clash pub rockers The 101-ers in Trouser Press magazine. Greatness-by-proximity is fair enough, because we should all be aware that the context in which we hear a song often dictates our feelings about it. Certainly, “London Calling” – the album session to which Silverton was privy, though he was not present for the recording of the actual title song – manifested in music the social unease at the end of Thatcher’s first year in power, the nuclear terror brought on by the Three Mile Island incident in the US, and foresaw and almost coincided with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. It is, fairly and squarely, a classic of its kind. (Mind, so is “Going Underground” by The Jam for similar reasons, and that one. released just a few weeks later, topped the UK charts.)

Having declared his own allegiance, Silverton then attempts to justify “London Calling’’’s claim to Official Anthem status by referencing and relegating the many other contenders, including not just The Clash’s own “London’s Burning “ but all those terrible pop songs called “London Town.” In doing so, he traces London lyrics all the way back to “the 1014 destruction and incineration of London Bridge by Norse invaders,” as depicted at the time by the court poet to King Cnut, Òttar The Black, whose chorus declared: “London bridge is broken down. Gold is won and bright renown.” Similarities to the well-known nursery rhyme - or indeed, “London Calling" - are apparently “happenstance,” says Silverton, given that Òttar’s “lyrics” were only recently translated. A more relevant similarity is that a radio station predating the BBC, and then the BBC’s wartime intro announcement and its global publication were all titled “London Calling,” something Silverton seems certain Strummer would have been aware of given his father’s diplomatic status.

Many would cite The Kinks’ “Waterloo Sunset” as the archetypal London song, but Silverton seems determined to seriously consider only those that name-check the city itself in their titles, and accordingly spends more time on two mid-20th Century runners-up: Noel Coward’s “London Pride,” which provides opportunity to connect Coward to FDR via Lord Mountbatten (it is that kind of book), and the same era’s music-hall standard, “Maybe It’s Because I’m A Londoner.” Neither sounds relevant in the 21st Century the way The Clash song does (or indeed, Ray Davies’ masterpiece, which is barely a decade older). Still, in making his argument for The Clash as standard bearers, Silverton is forced to question what it means to be a Londoner. He can never quite draw a conclusion. For that matter, neither can I, and I too was brought up there. Anyone?

Tony Fletcher, Wordsmith, posts twice a week. Subscribe to get the posts in your inbox; upgrade for just $6 a month/$60 a year or equivalent to get bonus posts and access to all the archives. You will also have access to the Crossed Channels podcast, including this episode on The Clash:

New Yorkers, at least on the surface, have no such doubts about their home city. New York, New York - so good they named it twice, remember - is big, brash, powerful, pervasive, monumental, magical, a veritable Tower of Babel, a homage to Mammon, an ego-ridden city that demands an egotistical anthem with equally grandiose qualities. The kind of anthem that can encapsulate all these attributes – or faults, depending on perspective – in a single line such as, “If I can make it there, I’m gonna make it anywhere,” as sung by someone who did just that, the Hoboken boy Ol’ Blue Eyes himself.

“Theme From New York New York” really was recorded by Sinatra (not in New York, despite early attempts, but ultimately in Hollywood, with a big orchestral arrangement by Don Costa) almost the same week as The Clash recorded “London Calling” in London. The reason that this comes as a shock to the average Joe – including Strummer, who was utterly bemused to learn of the coincidence, courtesy of the author years down the line – is not just because “Theme From New York New York” had also been recorded several years earlier by Liza Minnelli for the Martin Scorsese film of that name, a film (and soundtrack song) that flopped despite Minnelli and Robert de Niro’s apparent marquee draw. It sounds older because it was meant to sound older: New York New York was based on Scorsese’s favorite musical, the 1953 film The Band Wagon directed by Vincente Minnelli – yes, Liza’s father.

Liza’s mother, but of course, was Judy Garland, and by the kind of coincidence that are easily found in this book, it turns out that Sinatra had paid Garland’s “death bills” way back in 1969. Garland’s iconic status with the gay community led to the Stonewall Rebellion the same night as her death. That happened in New York City too, lest you need reminding. (The Stonewall Rebellion, that is; Garland died in London.)

There is more. At the time of making the movie New York, New York, Martin Scorsese was conducting an affair with Liza Minnelli; both were newly married at the time, though as you may have guessed, not to each other. (Liza was additionally running around with Mikhail Baryshnikov.) Scorsese saw New York New York as a “Valentine to Hollywood,” specifically that of Liza’s real-life parents, to the extent that, shooting the film in Hollywood so that a 1940s-era New York City could be reconstructed in an exaggerated style, he gave Liza her mother’s old dressing room. One suspects even Freud may have had to ponder the psychiatric ramifications of this one.

In the film New York, New York, the theme song is composed by Minnelli and De Niro as a songwriting partnership and married couple far more successful at the former relationship than the latter. In real life, the theme was composed, to order, by the duo of John Kander (music) and Fred Ebb (words), the latter who had written Minnelli’s nightclub act back in the 1960s, the duo of which had created the musical Cabaret, the one that in 1972 made Minnelli a film star in her own right and won her an Oscar in the process.

Nonetheless, they were still ultimately just songwriters for hire, and their early attempts at a “Theme From New York New York” were rejected for being too “airy.” They were close to being eclipsed from the commission completely until, in anger at the latest in-person rejection from Scorsese, Minnelli, De Niro and producer Irwin Winkler, they returned to Bronx-born Ebb’s Manhattan house and came up with the big, brash, bold five-note vamp that would become recognized world over, along with that opening personal proclamation, “Start spreading the news...” Take this, motherfuckers!

With the exception of the Stonewall connection, all of the above I garnered from this book: if Silverton excels at autoethnography in the early stages of the book, he triumphs with his research about New York (New York). Naturally, he then creates a near-Top 10 of rival contenders for this city’s Official Anthem status too. The closest commercial competition would be Jay-Z and Alicia Keyes 2009 worldwide chart topper “Empire State of Mind,” which was smart enough to namecheck almost every landmark in the city, and to reference Sinatra and the aforementioned lyric in the very first verse. (Silverton also gives a page-plus to The Dictator’s own “New York New York,” which I mention as that song’s composer, Andy Shernoff, is a good local friend of mine and hopefully delighted to receive the kudos.)

Neither “London Calling” nor “Theme From New York, New York” was a massive hit at the time. Sure, The Clash single was their biggest in the UK during their performing lifespan, by chart position, but it still stalled one place outside the Top 10. In the US, its only listing was in the Hot Dance Club Play chart (seriously!), though it would be the London Calling album’s finale, Mick Jones initially un-credited “Train In Vain,” the album’s real dance number, which would break though to the Hot 100’s Top 40 later in 1980. As for “Theme From New York, New York” (the comma is optional), Minnelli’s version halted outside the Hot 100, perhaps because, in one of those epic moments of bad timing, Scorsese’s heavily nostalgic film was released only a week before the proudly futuristic Star Wars rewrote cinema instantaneously. It’s also a little overwrought, as Minnelli has been known to be.

Sinatra’s co-option – some would say his rescue - of the theme song was but gradual, beginning only with the initial five-note vamp as his own opening theme, but after introducing the song into his set (in New York City, natch), he was soon forced to close with it. Similarly, his recording, once nailed and released, was a slow chart-burner, after which it would become his last Top 40 hit in the summer of 1980, a suitable coda to a cinematic career. Nonetheless, it still made only Number 32, a month or two after “Train In Vain” peaked at 23.

Chart positions come and go; legacies last forever. Both songs have endured to become deeply woven into their city’s cultural tapestry, regardless of whether mayors or legislatures can or have indeed declared them Official. It’s the people that make these choices, and the people, they have spoken, sung and shouted their approval.

London Calling New York New York is as bold and ambitious as the songs and the cities it describes. Its own legacy may not be quite so impactful, and not just because its publishers are independents. (Rocket 88 put the book out in the UK.) It can be an exhaustive read, with Silverton’s tangents and detours sometimes stretching the reader’s patience, and his tendency to closing out anecdotes with phrases like “Oh, pop music” gets tiring quickly, as does his endless assertion of the cultural capitals that “as one breathes out, the other breathes in.”" But his research, whether historic or contemporary, is impressive (he tracked down Fred Ebb, among others), and his love for the two cities self-evident.

Neither London nor New York, Silverton points out, was showing its best in 1979-1980, and they have changed considerably since. London has probably usurped New York as the most cosmopolitan metropolis in the world and is fast on its way to becoming another “city that never sleeps,” a reputation that NYC seems relatively willing to sacrifice – though to be fair, I no longer try and stay up all night when I’m there. (London is a different story!)

Both cities retain magical qualities, and, I suspect, until either of them drowns, they will continue to have songs continue to be written about them. Books, too. Silverton’s love letter to them deserve its own pride of place on their already heaving library shelves.

Enjoyed the read- who published your books?