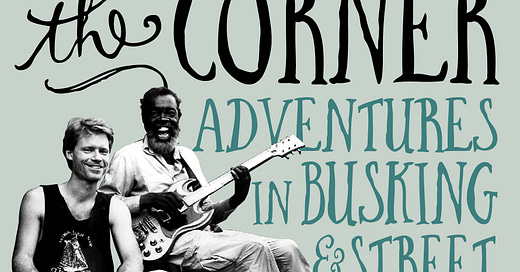

The Buskers' Song: Down On The Corner

A new book by Cary Baker gives the artful history of street singing its due

Whatever musical tastes we may consider unique, whatever personal introductions we may have had to live music and record collecting, chances are that before those tastes took hold, we were exposed to music in public, via someone(s) standing in the street performing either for change or for the fun of it. Call it busking, call it street singing… the form…