Was American Hardcore the most rebellious music ever?

A time capsule documentary film suggests that it was.

Monday night, I took the 20-minute drive to Saugerties for another of the Orpheum Theater’s Sonic Wave music movie Mondays.1 As sometimes the case, the film that was being shown – this week it was American Hardcore - can be viewed at home, but as is almost always the case, one knows it is going look and sound so much better on the big screen. And as often with these Sonic Wave events, especially when they are tagged as “Close Ups,” there was an additional reason to attend. This past Monday night, it was that a friend from my NYC days, Steven Blush, would be in attendance to talk about his role in the film. And in Blush’s case, that role was pivotal: he was author of the 2001 book American Hardcore that evolved into the 2006 film of the same name, for which Blush was credited as writer and producer; the film was directed, and expertly so, by Paul Rachman. Trailer below (hopefully; the very word hardcore is a red flag to search engines!).

I had never seen American Hardcore before. I was never part of that scene. I admired it, or at least acknowledged it, from afar; somehow my very new wave UK fanzine Jamming! was deemed hip enough in the States that I was to find myself on the mailing list for the ROIR cassette label, for Flipside magazine and more, all of which kept me informed, as did the occasional home-made mix tape from enthusiastic readers in the Americas. But I didn’t hear much of it, and what I did hear confused me as much as it fascinated me.

Like many in the UK, I had already been bowled over by the Dead Kennedys’ 1980 debut single “California Uber Alles” and its follow-up “Holiday In Cambodia,” though unlike many in the UK, I went to their debut UK show in late 1980 at the Music Machine, where I was somewhat disappointed that much of the set sounded, to my ears, like a primitive thrash, an impression confirmed by debut album Fresh Fruit For Rotting Vegetables.

That thrash, of course, was a form of hardcore punk, and when 16-year-old me interviewed band members Jello Biafra and East Bay Ray almost the day after that gig, I was promptly (re)schooled in not just American political and social culture, but the ability of US punk rock musicians to articulate that culture in an intellectual and yet everyman manner that, frankly, had no UK rival. Not Joe Strummer. Not Paul Weller. And certainly not Jimmy fucking Pursey, more of whom – sadly – anon.

Those who were part of the American Hardcore scene will no doubt want me to note that the Dead Kennedys were something of an anomaly musically, politically and commercially; the very fact that they had a UK label and were getting played on the radio as the scene was birthed was in fact almost anathema to hardcore’s very principals. They are also not interviewed in the film, one of its very few omissions, though Jello Biafra is prominent in the book, at least the 2010 Second Edition.

The actual hardcore scene depicted in the movie had its birth in the notion, right around the time that the Dead Kennedys were visiting England, that New York mid-70’s CBGB’s “punk” had been born out of artsy intellectualism that did not translate to more suburban and mundane environments and that the British punk that rapidly followed made little social sense to alienated suburban kids in conservative America, where Margaret Thatcher and the Queen were irrelevant names to rally against and the British “dole” did not exist, but the surfing and skateboarding cultures did.

Likewise, “skinny tie” new wave as perpetrated by The Knack or The Cars seemed no more challenging or threatening to the establishment than the existing soft rock/AOR hierarchy of Fleetwood Mac, The Eagles, Journey and others. However, the late 1980 election of Ronald Reagan with his Morning In America manifesto and the accompanying decade’s Greed Is Good mentality represented a much more obvious and, to those kids who had no desire to follow the social or musical script, dangerous threat to their no-futures and therefore served as a provocation requiring a reaction.

Those who had already made the cultural leap quickly discovered that to be a punk in the midst of this retro-conservative era was to invite trouble. In fact, it invited so much hostility that the more resolute among those who felt punk to be their calling became more confrontational in their music, their looks, and their attitude. As Jimmy Gestapo of NYC’s Murphy’s Law put it in the book, “Everybody got beat down so much for being Punk Rock that they became Hardcore. It was fun running round with spiked hair and bondage belt, but I got beat into shaving my head, putting boots on, and arming myself with a chain belt.” Or as Detroit’s Negative Approach put it more succinctly in an early song, they were “Ready to Fight.”

Musically it was the same story: punk, already basic by nature, was now stripped down to its (hard)core. To paraphrase Keith Morris of Circle Jerks and Black Flag from early in the movie, it did away with a song’s intro, outro, bridge/middle 8 and certainly did not brook any solos; it then condensed verse and chorus into one, and played what was left at a furiously fast and aggressive pace. Some songs were lucky to last a minute.

Hardcore was a scene pioneered by bands like Black Flag, Minor Threat, Bad Brains, Middle Class, 7 Seconds, SS Decontrol, D.O.A., the Minutemen, Suicidal Tendencies, T.S.O.L, Flipper, Fear and so many dozens, even hundreds more. It was a scene that arguably started on the west coast, where a San Fran fanzine called Damaged (also the title of Black Flag’s debut LP) inadvertently came up with the term, which the Vancouver (Canada, but still west coast) group D.O.A. then used for their debut album title, Hardcore ’81. Regardless of geographic origins, it quickly spread across the country; the list of acts above reflect as much.

Tony Fletcher, Wordsmith, posts twice a week. Subscribe to get the posts in your inbox; upgrade for just $6 a month/$60 a year or equivalent to get bonus posts and podcasts and access to all the archives. You will certainly receive your words-worth.

These groups toured an underground network of church basements, house concerts, rented rooms and the occasional actual venue that supported and encouraged the scene to blossom while remaining resolutely underground, counter to even the prevailing counterculture. Steve Blush was one of the kids whose lives was changed by it. An unusual scenester in as much as he’d been on a high school exchange trip to London, where he saw the Clash before they came to the States, he went on to attend college at George Washington University in D.C., with plans to be a lawyer. Instead, he found himself exposed to D.C.’s own Bad Brains and Minor Threat, and then to Black Flag’s pronouncement that success could be measured on non-economic terms.

Such a simple and powerful ethos ran counter even to the counterculture of the era, and it changed Blush’s path. Out went the conventional parental-approved career plans and in came a non-career as a D.C. hardcore gig promoter. Visiting bands often slept on Blush’s couch, as was the fashion (brought on by economy but also community) and in turn he became friends with many of them, which proved handy two decades down the line. When he moved up to NYC in the interim (he was originally from Jersey) and became a freelance music journalist, Blush also started a small magazine of own, called Seconds.

By that point, however, hardcore had mutated and dissipated, though it had hardly disappeared – CBGB’s put on Sunday hardcore matinees during my first several years in NYC (the late 1980s into the 1990s), and I was familiar with many of the groups and their members by name, if not by habitual listening. It is thanks to Blush’s determination to document a scene that was frequently passed over in the bigger history of (punk) rock that his well-received published oral history soon became such a riveting film.

American Hardcore’s cinematic triumph is that it reflects its subject matter. The film is itself fast, furious, loud and abrasive. Interviewees – and there are hundreds – are rarely allowed to ramble (unless they are Henry Rollins). They are interviewed everywhere – in their homes, on the street, in studios, at darkened desks, in parks in front of what seems to be a wedding, and quality of audio or constancy of look is irrelevant to allowing them their message and memories.

Live film clips – of which there are dozens, far more than you might have imagined were archived – are equally to the point, and they are riveting for documenting the birth of stagediving and slam-dancing with an intensity that was quickly forbidden from formal venues. There is no narration: Blush told me afterwards to my observation of this, that good documentaries don’t need a narration, a simple summary I perhaps always understood deep down but had never heard articulated in so few words.

While the movie accurately articulates the anger and alienation that fed the scene, its participants present as hilarious in hindsight. Most are unrepentant – indeed, in a post-screening conversation with local rock writer (and punk musician) Peter Aaron, Blush felt duty bound to inform viewers that some of the most extreme talking heads from the 20-year-old movie are now among the most socially conscious people you could meet – but their middle-aged refusal to compromise is delivered with a self-aware dark humor. The hardcore scene back then was full of damaged kids, and they were not in it for the pose: many were runaways or rejects, kids who gravitated from the suburbs to live in abandoned inner-city basements and poverty-strewn squats, and while some inevitably fell by the wayside, others turned out to be whip-smart and highly driven in the process, outsiders who finally found a way to fit in.

None of them were unafraid of violence. One of the most disconcerting film clips is from a Black Flag gig in which an audience member keeps trying to swipe at vocalist Henry Rollins, who eggs him along with a gleeful, even playful look on his face… until the antagonist’s guard is down, at which Rollins starts swinging at him from stage height with several southpaws that send the guy reeling. You can feel the force of Rollins’ fist all these years later, even from the back of a cinema. (The clip below is not that one, but it captures the band’s visceral energy and immediate popularity with arguably their most influential song.)

In other words, the hardcore movement was not a fucking Sham. Henry Rollins and all the other front men who took the brunt of audience aggression were no Jimmy Pursey style shitters. They didn’t seek to be figureheads or spokesmen, they had no initial interest in airplay or record deals, they weren’t on the make like some of the British punk bands, and accordingly their audiences treated them with a due mixture of social irreverence and respect. And as evidenced by that clip of Black Flag, if the audience’s irreverence did get too disrespectful, then unlike certain UK punk bands whose influence in the US frankly seems illogical, these bands knew how to handle it.

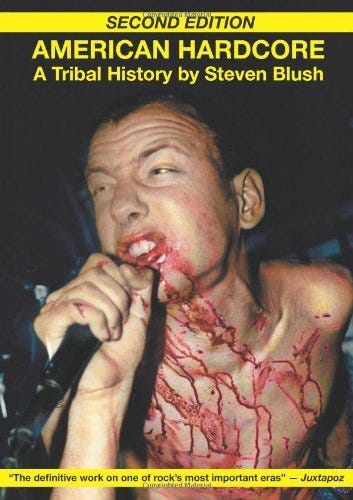

As all of this suggests, it was a scene in which the musicians were almost exclusively male, a subject that was only touched upon in the 2006 movie and would likely receive more attention now: indeed, one of just two few female band members interviewed for the film, Kira Roessler, quit Black Flag in 1985 after they released the record Slip It In, for its blatantly sexist title and imagery, per above. (With a six-minute opening song, it no longer fit the hardcore mold anyway.) Still, and for all that Ian McKaye’s Minor Threat song “Guilty of Being White” would later be seized upon by Polish ultra-nationalists and the like, hardcore was racially inclusive, Black punks were welcomed onto the scene.

Indeed, one of the scene’s most important bands – if you were on the east coast, probably the most important band – was Bad Brains, an all-Black group of punks who could also embrace proper JA-style reggae.. Their early release “Pay To Cum” is considered seminal; my Fanzine Podcast guest Jack Rabid named his zine after the song “The Big Takeover”; the Beastie Boys, initially a bratty hardcore band, chose their name to match the Bad Brains’ initials. That group’s importance made it all the sweeter that the band’s guitarist Dr. Know (who had never seen the film before although, like me and most others, he surely had the option to watch it at home, and even for free) was in attendance at the Orpheum, along with all manner of other former scenesters who have ended up living far from the suburbs that fueled their anger.

American Hardcore the film traverses the country by way of an animated map created by artist John Vondracek which, in his post-screening discussion, Blush credits as being the “thing” that got the movie into Sundance when it was first hoisted onto the festival circuit. The map helps trace the music’s different strands – from the straight edge stance popularized by east coast bands and widely associated with Ian McKaye and his groups Teen Idles, Minor Threat and Fugazi, through to the brutality foisted on the LA punks by the LA police, violence which was typically blamed on the audience by a sensationalist and complicit media.

By jumping all over the place like this, attempting to cover the multiple corners and crevices of the geographical and cultural map without forewarning or subsequent judgement, the film replicates the speed and fury of the gigs themselves. Those gigs are explosive, challenging the very notion of musicality; the sound is wild, the audiences wilder, the slam-dancing and stagediving insane.

But above all, it’s rebellious. Groups named themselves Reagan Youth (whose tragic story might explain the lack of members depicted onscreen), Millions of Dead Cops, and of course Dead Kennedys, titled their songs “Smash The State,” “Screaming At A Wall,” “John Wayne Was A Nazi,” and they hit out at societal norms, authority figures, and especially, the Reagan Doctrine, the President defiled and defaced on the fliers and fanzines that disseminated the message, insulted in songs.

When Reagan was reelected in a landslide in 1984, some of the fizz went out of hardcore. You can only kick against the pricks for so long before your feet hurt. Many groups broke up. But some bands and/or their individual members reacted with renewed and reinvigorated commitment to whatever fragile manifesto hardcore represented – e.g. Black Flag’s Greg Ginn and Minor Threat’s Ian McKaye with their record labels, SST and Dischord respectively. Others soldiered on through the present day as ever they were (D.O.A. are still going strong 45 years down the line). Another subset expanded their musical oeuvre and helped create a sound known as hardcore metal: NYC’s Cro-Mags are considered pioneers of this vein. (It is no coincidence that in 2003, Metallica would hire Suicidal Tendencies’ bassist Rob Trujillo, who is with them to this day.)

There is even somehow considered a direct connection between the skinhead look of hardcore and the retrospectively comical Aquanet overdose of hair metal – which is noted in the movie by Guns N’ Roses’ Duff McKagan, an early member of the LA scene, and further explored in Blush’s book about the latter scene. (The author is also about to complete his trilogy, When Rock Met Disco/Reggae/Hip-Hop; I was interviewed for the Reggae one.) Blush took some understandable heat for writing the Hair Metal book, but he defended himself at the Orpheum by describing his work as “cultural anthropology,” a category I would likewise (love to) consider my own writings to fall under. [Below you can hear him discuss his various books on a podcast that draws the connection. There is also a good short Miami Herald interview about the film on his website.]

Blush, like me, is now in his sixties. Most of the musicians who have survived will be that age or older. This allows us to reflect on whether there will ever be a scene quite so confrontational, especially in the States. After all, if Trump’s first term couldn’t generate a musical protest movement, what chance does a second term have with a four-year in the interim that allowed for amnesia among the voters? This inevitably brings us to the subject of music’s reduced status in most contemporary young peoples’ lives, its inability to weave a socially confrontational and coherent narrative, let alone produce a proper subculture, even though independent music itself is still full of risk and rebellion if you look and listen out for it.

In the UK, where I grew up during American Hardcore’s golden years, such a movement did not exist. There was that whole Real Punk/Punk’s Not Dead movement, but I always found the UK leather jacket and mohawk brigade to be a pose first and foremost, while musically, it emulated the bad punk of the worst bands of 77 and 78. At least US hardcore actually invented something that took the Ramones’ artsy minimalism to new proletariat extremes.

There was, however, in the UK, a scene that rivaled American hardcore for musical intensity, social shock value, and (unfortunately) attendant gig violence largely brought on by those who sought to crush it. I am talking about the anarcho-punk movement as led by Crass, which inspired countless British kids of all classes, and which continues to reverberate down the generations. (Early live clip above.)

However, for all its lasting influence, then just as in the States, there is no scene that causes consternation in the way Crass and their disciple groups did back in the 1980s. There is no Minor Threat to the system within current music, let alone a major one. As such, American Hardcore is not just a riveting, revolting and duly loud documentary (this tinnitus sufferer was glad to bring his earplugs), but a true time capsule, a reminder of an era when rebellion was not for sale, and commitment to the cause was total.

(This is the same venue where I recently held my Smiths presentation, and before that those on R.E.M. and Keith Moon; we are fortunate to have such an incredible music-minded theatre with such brave programming in our vicinity. Truly, I don’t know that NYC itself or London has a consistent program like this.)