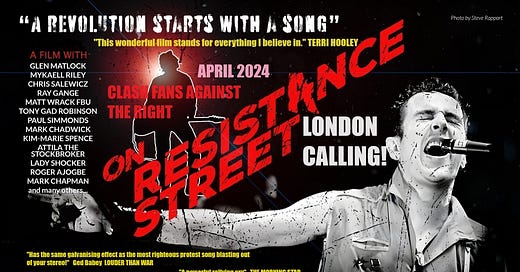

On Resistance Street

A film by Clash Fans Against The Right documents music's historical fight for racial harmony.

I grew up in a racist society.

Thankfully, the formative years of my London life were relatively free of prejudice: in the early 70s reggae and soul music had as big a presence on the British pop charts as glam, my mum made friends with the West Indian and Asian immigrants she taught in South London comprehensive schools, my surrogate big brother Jeffrie…